Advancing alpine hydrological modeling through scale-appropriate complexity and automated parameter regionalization

Supervisor: Karsten SCHULZ

Project assigned to: Caroline EHRENDORFER

Hydrological models are essential tools for water resource management and enable the simulation of explicit hydrological processes across catchments. While machine learning models such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks have gained popularity in recent years in predicting a single variable such as runoff (Kratzert et al. 2019), the application of physically-based (e.g., Alpine3D (Lehning et al. 2006) + StreamFlow (Gallice et al. 2016)) or (semi-) distributed conceptual models (e.g., COSERO (Herrnegger et al. 2015), mHM (Samaniego et al. 2010)) still have their advantages. These include their parsimony and the explicit representation of spatially distributed system states and fluxes, which are not continuously measurable at a large scale but of high relevance for any number of environmental, hydrological or ecological studies and applications (e.g., Newman et al. 2015, Zink et al. 2017, Zeitfogel et al. 2025). However, two fundamental challenges persist: (1) determining the appropriate level of model complexity for different applications, particularly in alpine regions where snow and ice processes dominate, and (2) estimating physically meaningful parameters when scaling models from well-studied catchments to large, heterogeneous domains.

While physically-based energy balance (EB) models provide detailed process representation, their computational demands often limit their application to small catchments or short time periods (Horton et al. 2022, Mott et al. 2023, von der Esch et al. 2025). Conversely, conceptual models using temperature index approaches offer computational efficiency, but their simplified process representations may inadequately capture feedbacks governing alpine hydrology under warming climates (Warscher et al. 2013, Ragettli et al. 2014, Carletti et al. 2022). Previous efforts to couple conceptual models with physically-based snow models (e.g., Kobierska et al. 2013, Gallice et al. 2016, Shakoor et al. 2018, Carletti et al. 2022) aim to capture the advantages of both approaches, yet questions remain about when such added complexity yields meaningful improvements in predictive skill.

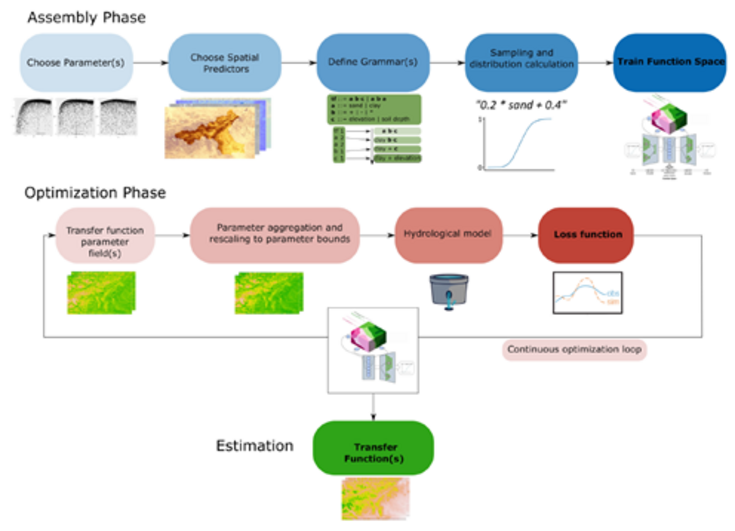

At the regional scale (several thousand km²), EB approaches reach their limits and conceptual models become the predominant choice. However, their parameterization remains a significant challenge, particularly when dealing with large spatial domains and ungauged basins (Parajka et al. 2005, Hrachowitz et al. 2013). Parameter transfer functions (TFs), which relate model parameters to physiographic catchment characteristics (Abdulla et al. 1997, Seibert 1999, Parajka et al. 2005) offer a solution but have historically required extensive expert knowledge and refinement over years (Samaniego et al. 2010, Kumar et al. 2013, Thober et al. 2019). The Function Space Optimization (FSO, Feigl et al. 2020) offers an automated method for estimating TFs, demonstrating success in Germany (Feigl et al. 2022). However, questions remain about its generalizability across different models and regions, and existing applications don’t include evaluation beyond discharge performance.

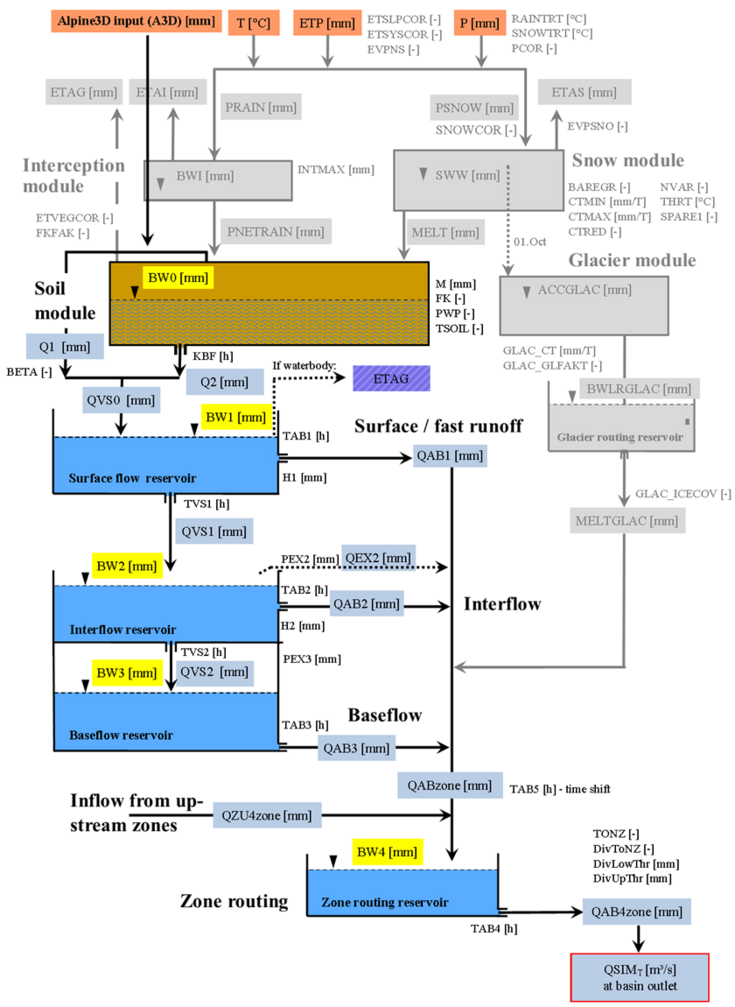

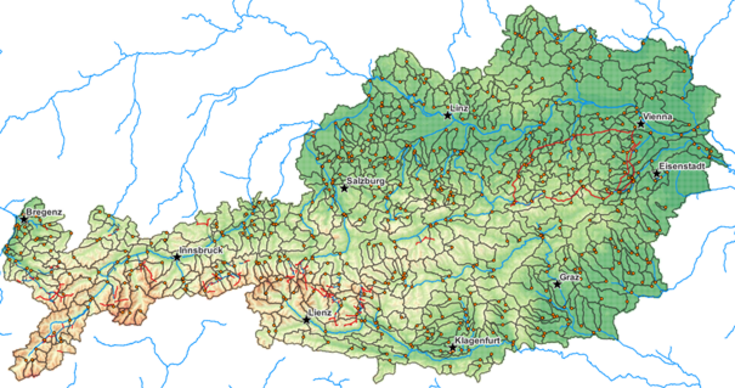

This research addresses these knowledge gaps through a multi-scale investigation of hydrological modeling in alpine Austria, progressing from detailed process understanding to large-scale application. First, high-alpine case studies using the COSERO model (Herrnegger et al. 2015) in both standalone and coupled configuration with the physically-based Alpine3D model (Lehning et al. (2006), see Figure 1) across the case study catchments of the Kölnbrein and Schlegeis reservoirs will establish when increased model complexity and sub-daily temporal resolution yield meaningful improvements in predictive skill. Second, once the necessary complexity to adequately account for snow-hydrological processes in alpine regions has been established in the case study setting, COSERO will be upscaled to model the entire Austrian domain (~92 000 km², see Figure 2). This will likely reveal the practical limitations of traditional calibration approaches when transferring model parameters across hydroclimatic regimes. Third, the Function Space Optimization (FSO, see Figure 3) framework will be implemented to estimate transfer functions for COSERO parameters, providing evidence regarding the method's applicability across different model structures and geographical regions.

Three research questions guide this work:

RQ1: Under which conditions (temporal resolution, process representation, target variables) does coupling COSERO with the energy-balance model Alpine3D yield meaningful improvements over the standalone conceptual model in glacierized catchments?

RQ2: Can traditional parameter calibration approaches adequately represent Austria's diverse hydrological regimes (~92 000 km²), and what are the primary barriers to transferring parameters across spatial scales and hydroclimatic gradients?

RQ3: Does the Function Space Optimization (FSO) framework successfully estimate transfer functions for COSERO that improve both runoff predictions and the representation of other water balance components (snow, evapotranspiration, groundwater recharge) compared to traditional calibration?

Success would provide novel insights into scaling and parameterization approaches in alpine hydrological modeling. This research represents an important step toward making process-informed hydrological predictions across diverse scales and applications – from understanding snow and ice processes in individual high-alpine catchments to assessing climate change impacts on water resources across a large regional domain.

Figure 1. The COSERO and coupled COSEROxAlpine3D schematic overview, including model parameters, system states and fluxes. The grey components are not active in the coupled version. Instead, Alpine3D covers the modeling of snow and glacier processes and the output is provided as a new input to the modified COSERO.

Figure 2. Modeling domain of the Austrian-wide COSERO model, including the 630 LamaH basin borders and gauging stations (Klingler et al. 2021).

Figure 3. Workflow oft the Function Space Optimization in two steps: The assembly phase, and the optimization phase. After the VAE has been trained, a continuous optimization algorithm samples from the function space and estimates the best transfer function(s) (figure by Feigl et al. (2020)).

Literatur

Abdulla, F. A. and Lettenmaier, D. P. (1997). Development of regional parameter estimation equations for a macroscale hydrologic model. Journal of Hydrology197(1): 230-257. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1694(96)03262-3.

Carletti, F., Michel, A., Casale, F., Burri, A., Bocchiola, D., Bavay, M. and Lehning, M. (2022). A comparison of hydrological models with different level of complexity in Alpine regions in the context of climate change. Hydrology Earth System Sciences 26(13): 3447-3475. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-26-3447-2022.

Feigl, M., Herrnegger, M., Klotz, D. and Schulz, K. (2020). Function space optimization: A symbolic regression method for estimating parameter transfer functions for hydrological models. Water Resources Research 56(10): e2020WR027385. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR027385.

Feigl, M., Thober, S., Schweppe, R., Herrnegger, M., Samaniego, L. and Schulz, K. (2022). Automatic regionalization of model parameters for hydrological models. Water Resources Research 58(12): e2022WR031966. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1029/2022WR031966.

Gallice, A., Bavay, M., Brauchli, T., Comola, F., Lehning, M. and Huwald, H. (2016). StreamFlow 1.0: An extension to the spatially distributed snow model Alpine3D for hydrological modelling and deterministic stream temperature prediction. Geoscientific Model Development 9(12): 4491-4519. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-9-4491-2016.

Herrnegger, M., Senoner, T., Klotz, D., Wesemann, J., Nachtnebel, H. P. and Schulz, K. (2015). RAINFALL-RUNOFF-MODEL COSERO Handbook 2015.2.

Horton, P., Schaefli, B. and Kauzlaric, M. (2022). Why do we have so many different hydrological models? A review based on the case of Switzerland. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Water 9(1): e1574. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/wat2.1574.

Hrachowitz, M., Savenije, H., Blöschl, G., McDonnell, J. J., Sivapalan, M., Pomeroy, J., Arheimer, B., Blume, T., Clark, M. and Ehret, U. (2013). A decade of Predictions in Ungauged Basins (PUB)—a review. Hydrological Sciences Journal58(6): 1198-1255. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2013.803183.

Klingler, C., Schulz, K. and Herrnegger, M. (2021). LamaH| Large-Sample Data for Hydrology and Environmental Sciences for Central Europe. Earth System Science Data Discussions 2021: 1-46. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-13-4529-2021.

Kobierska, F., Jonas, T., Zappa, M., Bavay, M., Magnusson, J. and Bernasconi, S. M. (2013). Future runoff from a partly glacierized watershed in Central Switzerland: A two-model approach. Advances in Water Resources 55: 204-214. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advwatres.2012.07.024.

Kratzert, F., Klotz, D., Shalev, G., Klambauer, G., Hochreiter, S. and Nearing, G. (2019). Towards learning universal, regional, and local hydrological behaviors via machine learning applied to large-sample datasets. Hydrology Earth System Sciences 23(12): 5089-5110. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-23-5089-2019.

Kumar, R., Samaniego, L. and Attinger, S. (2013). Implications of distributed hydrologic model parameterization on water fluxes at multiple scales and locations. Water Resources Research 49(1): 360-379. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1029/2012WR012195.

Lehning, M., Völksch, I., Gustafsson, D., Nguyen, T. A., Stähli, M. and Zappa, M. (2006). ALPINE3D: a detailed model of mountain surface processes and its application to snow hydrology. Hydrological Processes: An International Journal 20(10): 2111-2128. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.6204.

Mott, R., Winstral, A., Cluzet, B., Helbig, N., Magnusson, J., Mazzotti, G., Quéno, L., Schirmer, M., Webster, C. and Jonas, T. J. F. i. E. S. (2023). Operational snow-hydrological modeling for Switzerland. 11: 1228158. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2023.1228158.

Newman, A. J., Clark, M. P., Sampson, K., Wood, A., Hay, L. E., Bock, A., Viger, R. J., Blodgett, D., Brekke, L. and Arnold, J. (2015). Development of a large-sample watershed-scale hydrometeorological data set for the contiguous USA: data set characteristics and assessment of regional variability in hydrologic model performance. Hydrology Earth System Sciences 19(1): 209-223. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-19-209-2015.

Parajka, J., Merz, R. and Blöschl, G. (2005). A comparison of regionalisation methods for catchment model parameters. Hydrology Earth System Sciences 9(3): 157-171. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-9-157-2005.

Ragettli, S., Cortés, G., McPhee, J. and Pellicciotti, F. (2014). An evaluation of approaches for modelling hydrological processes in high‐elevation, glacierized Andean watersheds. Hydrological Processes 28(23): 5674-5695. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/hyp.10055Digital.

Samaniego, L., Kumar, R. and Attinger, S. (2010). Multiscale parameter regionalization of a grid‐based hydrologic model at the mesoscale. Water Resources Research46(5). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1029/2008WR007327.

Seibert, J. (1999). Regionalisation of parameters for a conceptual rainfall-runoff model. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 98-99: 279-293. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1923(99)00105-7.

Shakoor, A., Burri, A., Bavay, M., Ejaz, N., Ghumman, A. R., Comola, F. and Lehning, M. (2018). Hydrological response of two high altitude Swiss catchments to energy balance and temperature index melt schemes. Polar Science 17: 1-12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polar.2018.06.007.

Thober, S., Cuntz, M., Kelbling, M., Kumar, R., Mai, J. and Samaniego, L. (2019). The multiscale routing model mRM v1. 0: Simple river routing at resolutions from 1 to 50 km. Geoscientific Model Development 12(6): 2501-2521. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-12-2501-2019.

von der Esch, A., Huss, M., van Tiel, M., Berg, J. and Farinotti, D. (2025). Modelling runoff in a glacierized catchment: the role of forcing product and spatial model resolution. Hydrology Earth System Sciences 29(22): 6761-6780. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-29-6761-2025.

Warscher, M., Strasser, U., Kraller, G., Marke, T., Franz, H. and Kunstmann, H. (2013). Performance of complex snow cover descriptions in a distributed hydrological model system: A case study for the high Alpine terrain of the Berchtesgaden Alps. Water resources research 49(5): 2619-2637. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/wrcr.20219.

Zeitfogel, H., Herrnegger, M. and Schulz, K. (2025). Regional-scale assessment of groundwater recharge and the water balance for Austria. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies 59: 102297. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2025.102297.

Zink, M., Kumar, R., Cuntz, M. and Samaniego, L. (2017). A high-resolution dataset of water fluxes and states for Germany accounting for parametric uncertainty. Hydrology Earth System Sciences 21(3): 1769-1790. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-21-1769-2017.