Deep Learning in Fluvial Flood Forecasting and Simulation

Supervisor: Karsten SCHULZ

Project assigned to: Oliver KONOLD

Fluvial floods are among the most impactful natural disasters worldwide, representing the most common disaster type (Razavi et al., 2020) and one of the most serious natural hazards (UNDRR, 2019). Between 2000 and 2018, an estimated 255–290 million people were directly affected by flooding events (Tellman et al., 2021), with increasing trends observed across Central Europe (Blöschl, 2022; Haslinger et al., 2025; Kemter et al., 2020). The causes of fluvial floods are complex, encompassing atmospheric processes such as heavy rainfall and rapid snowmelt, as well as catchment-specific factors including soil moisture conditions (Merz et al., 2021). Climate change is expected to further increase both the magnitude and spatial extent of floods (Kemter et al., 2020), making operational flood forecasting systems paramount as integral components of flood risk management (European Union, 2007).Such systems function as rainfall-runoff models operating in real-time to predict the likelihood, timing, and severity of floods (Jain et al., 2018).

Figure 1: 2002 Danube flood at village Ybbs (meinbezirk.at, 2022)

Hydrological models can be categorized into physically based, conceptual, and data-driven approaches, with artificial neural networks (ANNs) representing a powerful subset of the latter (Klingler et al., 2022; Krogh, 2008). The emergence of large-sample hydrological datasets, advances in deep learning methods, and enhanced GPU hardware have enabled significant breakthroughs, particularly through the work of Kratzert et al. (2018), which demonstrated the potential of Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks to outperform traditional hydrological models in both gauged and ungauged catchments. LSTMs are a specialized form of recurrent neural networks designed for sequential time-series data(Hochreiter and Schmidhuber, 1997), utilizing gating mechanisms—input, forget, and output gates—to control information flow through cell and hidden states (Gers et al., 1999). This architecture enables LSTMs to retain relevant information over extended time periods and capture temporal dependencies inherent in hydrological processes. LSTMs are particularly suited for hydrology as they mirror the storage-cell concepts found in conceptual models (Kratzert et al., 2018) and can be interpreted as nonlinear state-space models. Their capacity to extract patterns from large, heterogeneous datasets and generalize across different hydrological regimes has been demonstrated extensively (Kratzert et al., 2019, 2024). A major advantage of deep learning systems is their ability to simultaneously integrate multiple data sources in a single model run, dynamically adjusting to spatial and temporal inconsistencies across inputs to enhance prediction accuracy (Kratzert et al., 2021).

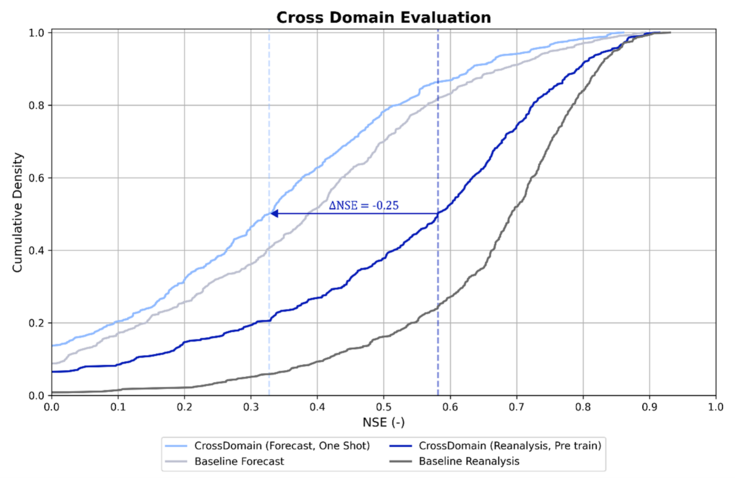

However, significant challenges remain. Hydrological processes are inherently governed by their spatial and temporal context(Gupta et al., 1986), presenting persistent challenges in model development. While deep learning models offer promising capabilities for bridging scale gaps and can process input data at various temporal resolutions (Gauch et al., 2021), most current approaches remain spatially lumped, treating catchments as uniform units and limiting the representation of intra-catchment variability. Additionally, operational forecasting depends on meteorological forecasts from numerical weather prediction models that typically exhibit lower accuracy and higher uncertainty compared to reanalysis data (Konold et al., 2025; Lavers et al., 2021). These biases, stemming from model resolution, data assimilation techniques, and orographic effects (Haiden et al., 2024), can propagate through hydrological models and lead to unreliable runoff forecasts, particularly under extreme conditions critical for early warning systems.

Figure 2: Cumulative Density Function of Nash Sutcliffe Efficiency values for a Cross Domain Evaluation Experiment, depicting the bias propagation from meteorological forecasts in flood forecasting deep learning models. The comparison includes a Pre trained model on five meteorological reanalysis variables (dark blue), a One Shot (direct application without fine-tuning) based on the weights of a Pre trained model with equal five meteorological forecasting variables and baselines (grey). The vertical dashed lines depict the median NSE for each experiment. The blue arrow shows the performance decrease at median NSE when applying cross domain evaluation. (Konold et al., 2025)

Given the current state of the art as outlined above, the main research questions (RQ) of the PhD thesis are:

RQ 1: How to reduce the meteorological forecast induced bias in runoff predictions with deep learning?

RQ 2: Has incorporating observed meteorological (station) data an impact on simulation quality?

RQ 3: How to leverage spatially distributed information in an AI model?

References

Blöschl, G.: Three hypotheses on changing river flood hazards, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 26, 5015–5033, doi.org/10.5194/hess-26-5015-2022, 2022.

European Union: Directive 2007/60/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2007 on the assessment and management of flood risks (Text with EEA relevance, 2007.

Gauch, M., Kratzert, F., Klotz, D., Nearing, G., Lin, J., and Hochreiter, S.: Rainfall–runoff prediction at multiple timescales with a single Long Short-Term Memory network, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 25, 2045–2062, doi.org/10.5194/hess-25-2045-2021, 2021.

Gers, F. A., Schmidhuber, J., and Cummins, F.: Learning to Forget: Continual Prediciton with LSTM, 1999.

Gupta, V. K., Rodríguez-Iturbe, I., and Wood, E. F. (Eds.): Scale Problems in Hydrology, Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-4678-1, 1986.

Haiden, T., Janousek, M., Vitart, F., Tanguy, M., Prates, F., and Chevallier, M.: Evaluation of ECMWF forecasts, 2024.

Haslinger, K., Breinl, K., Pavlin, L., Pistotnik, G., Bertola, M., Olefs, M., Greilinger, M., Schöner, W., and Blöschl, G.: Increasing hourly heavy rainfall in Austria reflected in flood changes, Nature, 639, 667–672, doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-08647-2, 2025.

Hochreiter, S. and Schmidhuber, J.: Long Short-Term Memory, Neural Computation, 9, 1735–1780, doi.org/10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735, 1997.

Jain, S. K., Mani, P., Jain, S. K., Prakash, P., Singh, V. P., Tullos, D., Kumar, S., Agarwal, S. P., and Dimri, A. P.: A Brief review of flood forecasting techniques and their applications, International Journal of River Basin Management, 16, 329–344, doi.org/10.1080/15715124.2017.1411920, 2018.

Kemter, M., Merz, B., Marwan, N., Vorogushyn, S., and Blöschl, G.: Joint Trends in Flood Magnitudes and Spatial Extents Across Europe, Geophysical Research Letters, 47, e2020GL087464, doi.org/10.1029/2020GL087464, 2020.

Klingler, C., Feigl, M., Linsbichler, T., Frey, S., and Schulz, K.: Potenzial von Machine Learning bei der kurzfristigen Leistungsprognose innerhalb einer Laufkraftwerkskette, Österr Wasser- und Abfallw, 74, 224–240, doi.org/10.1007/s00506-022-00849-6, 2022.

Konold, O., Feigl, M., Podest, P., Klingler, C., and Schulz, K.: BiasCast: Learning and adjusting real time biases from meteorological forecasts to enhance runoff predictions, doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2025-4978, 27 November 2025.

Kratzert, F., Klotz, D., Brenner, C., Schulz, K., and Herrnegger, M.: Rainfall–runoff modelling using Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 22, 6005–6022, doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-6005-2018, 2018.

Kratzert, F., Klotz, D., Shalev, G., Klambauer, G., Hochreiter, S., and Nearing, G.: Towards learning universal, regional, and local hydrological behaviors via machine learning applied to large-sample datasets, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 23, 5089–5110, doi.org/10.5194/hess-23-5089-2019, 2019.

Kratzert, F., Klotz, D., Hochreiter, S., and Nearing, G. S.: A note on leveraging synergy in multiple meteorological data sets with deep learning for rainfall–runoff modeling, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 25, 2685–2703, doi.org/10.5194/hess-25-2685-2021, 2021.

Kratzert, F., Gauch, M., Klotz, D., and Nearing, G.: HESS Opinions: Never train a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network on a single basin, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 28, 4187–4201, doi.org/10.5194/hess-28-4187-2024, 2024.

Krogh, A.: What are artificial neural networks?, Nat Biotechnol, 26, 195–197, doi.org/10.1038/nbt1386, 2008.

Lavers, D. A., Harrigan, S., and Prudhomme, C.: Precipitation Biases in the ECMWF Integrated Forecasting System, Journal of Hydrometeorology, 22, 1187–1198, doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-20-0308.1, 2021.

meinbezirk.at: Donauhochwasser 2002! Zweite Welle vom Mo 12. bis Do 15. August!, 2022.

Merz, B., Blöschl, G., Vorogushyn, S., Dottori, F., Aerts, J. C. J. H., Bates, P., Bertola, M., Kemter, M., Kreibich, H., Lall, U., and Macdonald, E.: Causes, impacts and patterns of disastrous river floods, Nat Rev Earth Environ, 2, 592–609, doi.org/10.1038/s43017-021-00195-3, 2021.

Razavi, S., Gober, P., Maier, H. R., Brouwer, R., and Wheater, H.: Anthropocene flooding: Challenges for science and society, Hydrological Processes, 34, 1996–2000, doi.org/10.1002/hyp.13723, 2020.

Tellman, B., Sullivan, J. A., Kuhn, C., Kettner, A. J., Doyle, C. S., Brakenridge, G. R., Erickson, T. A., and Slayback, D. A.: Satellite imaging reveals increased proportion of population exposed to floods, Nature, 596, 80–86, doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03695-w, 2021.

UNDRR: Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction, United Nations, 1 pp., 2019.