The Framing of Sustainability in the Food supply Chain

SUPERVISOR: Petra RIEFLER

PROJECT ASSIGNED TO: Magdalena THUR

Research Background

As a normative research tradition, sustainability sciences aim to support the advancement towards sustainability goals such as the 2°-mark of the Paris Agreement (Messerli et al., 2019). Research highlights that collective action by many stakeholders is a prerequisite for achieving such goals (IPCC, 2021). Thus, involving stakeholders from various backgrounds to foster collaborative knowledge is one of the key missions of sustainability sciences (University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, 2023).

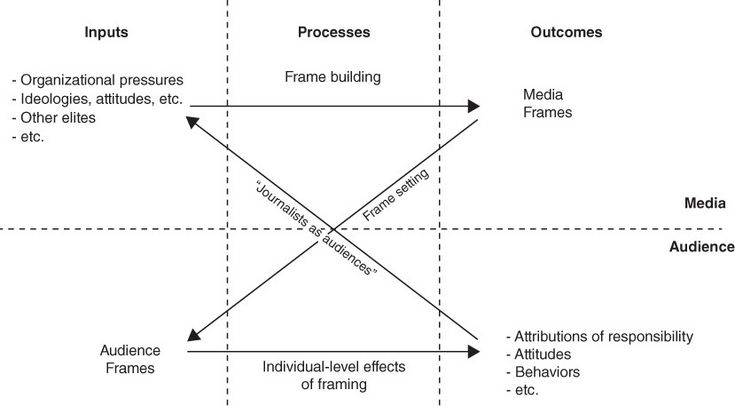

Framing literature documents that the way collective problems are framed may support or hinder actors’ engagement in such collective efforts (Benford & Snow, 2000; Crompton et al., 2010; O’Neil & Kendall-Taylor, 2018; Wardekker & Lorenz, 2019). Conceptually, frames can take form of mental (i.e., cognitive) frames or media frames (i.e., symbolic manifestations) (Chong & Druckman, 2007; Hallahan, 1999; Kahneman & Tversky, 1984; Reese, 2018; B. Scheufele, 2004). Accordingly, framing is traditionally anchored in the psychological and sociological disciplines (Guenther et al., 2023; Reese, 2018), but has since expanded to a multitude of disciplines, such as informatics, economic sciences and philosophy (Dahinden, 2018; Guenther et al., 2023; Ziem, 2018). Figure 1 links the inputs and outcomes of the framing process.

Figure 1: Inputs, Processes and Outcomes in Framing (O’Neill & Schäfer, 2018)

Seminal literature from the sociological research tradition of framing defines “to frame” as to “select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text” (Entman, 1993, p. 52). The frame thus defines the problem and its possible causes and consequences. It can also morally judge associated actors, suggest appropriate action and assign responsibilities among agents (Entman, 1993; Matthes & Kohring, 2008; Van Gorp, 2009). As such, the forms and number of actions taken by the collective is largely determined by how a phenomenon is framed (Benford & Snow, 2000; Chong & Druckman, 2007; Entman, 2007; Hallahan, 1999). For example, climate change activists frame the phenomenon as a political emergency in order to convey urgency and propagate civic support (Svensson & Wahlström, 2023; Wehling, 2018).

Abstract concepts and complex phenomena require to be framed in order to become intelligible (Bateson, 1972; Goffman, 1974; Wehling, 2018) - a process called “meaning-making” (B. Scheufele, 2004; Dietram A. Scheufele & Tewksbury, 2007). The abstract concept of “sustainability” thence is subject to this process (Janoušková et al., 2019; Ness, 2020). Reflecting the plurality of domains the term is applied to, sustainability is understood in multiple ways by diverse actors (Barr & Gilg, 2006; Béné et al., 2019; Rust et al., 2021; Van Gorp & van der Goot, 2012). Against the above, these underlying understandings are critical for actors’ engagement in subsequent actions (Crompton et al., 2010; Janoušková et al., 2019).

In this light, the role of framing appears particularly relevant to better understand actors’ stance towards the common goal of a transitions towards sustainability. The research project presented here will therefore utilize the concept of framing to illuminate transitions to sustainability from a perspective of communication sciences.

Research Gaps

The concept of sustainability will serve as an object of research that will be approached from the conceptual viewpoint of framing. Reviews on framing literature have identified several research gaps (Guenther et al., 2023; Matthes, 2009; D. A. Scheufele & Iyengar, 2014). Three of them are highlighted here, as they represent opportunities to simultaneously advance transitions to sustainability, as well as framing research.

First, extant literature on frame analyses has mainly focused upon media frames, while research on mental frames has been scarce (D’Angelo, 2018a; Guenther et al., 2023; Matthes, 2009). As this research gap is particularly concerned with actors and audiences, it is particularly relevant for understanding stakeholder’s engagement for sustainability goals (Benford & Snow, 2000; Crompton et al., 2010; O’Neil & Kendall-Taylor, 2018). Furthermore, mental frames lend themselves for implementing transdisciplinary elements into the research design, which are vital for sustainability sciences (University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna, 2023).

Second, frames have often been analyzed on the basis of specific topical discourses. However, certain framings can be topic-independent by following culturally established narrative patterns (Brüggemann & D’Angelo, 2018; D’Angelo, 2018b; Dahinden, 2018; D. A. Scheufele & Iyengar, 2014). Those “generic frames” emerge from communicator’s processing and reformulating of issue-specific information in a particular organizational environment (D’Angelo, 2018b). For example, a Journalist in the newsroom environment may reformulate incoming information about a climate protest road block along the lines of the “conflict”-frame, a generic frame that highlights the event from the perspectives of conflicting parties (e.g. protesters vs. road users) (Dahinden, 2018). So far, generic frames have attained less scientific attention than thematic frames (Guenther et al., 2023; Matthes, 2009; D. A. Scheufele & Iyengar, 2014). However, because they may impede appropriate action by obscuring relevant information, understanding their functionalities is relevant for transitions to sustainability.

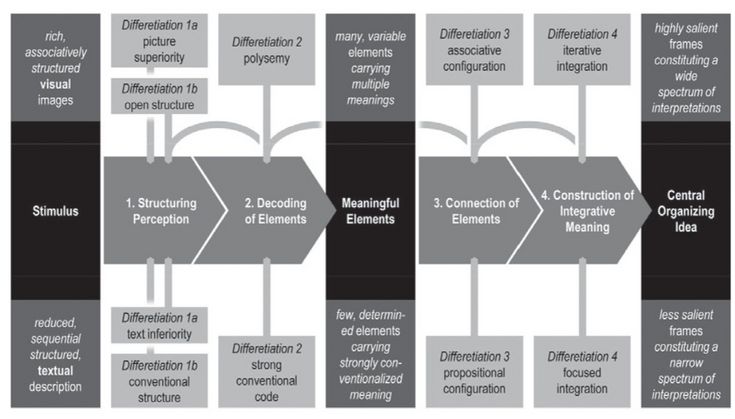

Third, media frames can be constructed with a multitude of different modes. Recently, framing theorists point towards the relevance of visual content as a mode of framing (S. Geise & Lobinger, 2013; Iorgoveanu & Corbu, 2011; Rodriguez & Dimitrova, 2011; D. A. Scheufele & Iyengar, 2014). In comparison to text, visuals suggest ways of looking at an issue in an associate, rather than an argumentative manner, and trigger stronger emotional and affective responses (Bock, 2020; Coleman, 2009; Müller, 2013). Figure 2 illustrates the process of framing in regards to visual and linguistic stimuli.

Figure 2: Generalized frame processing model for visual and linguistic stimuli (Geise & Baden, 2015)

Images can enhance, but also limit imagination via different visual attributes such as content, style, symbolism and ideology (Rodriguez & Dimitrova, 2011). For instance, the IPCC reports mainly visualize negative impacts distant in space and time. This visual focus stages climate change “somewhere in the future”, while missing out on showing who is responsible for causes, who is impacted, who needs to adapt, and who can provide remedies (Wardekker & Lorenz, 2019). To implement visual modes into the framing research paradigm, researchers call for (i) conceptual work including related literature streams such as Visual Studies, as well as (ii) developing adequate methodological approaches (Bock, 2020; S. Geise & Lobinger, 2013). Investing into visual framing research can help to adequately illustrate transitions to sustainability in a solution-oriented manner.

Research Questions

Against the above, the dissertation project aims to advance framing literature using the context of sustainability transition. For this purpose, the thesis takes an interdisciplinary approach bridging sustainability sciences and communication sciences to make conceptual as well as substantive contributions to the fields. At a conceptual level, tentative research questions comprise:

- How can the translation of mental frames into media frames, and vice-versa, be operationalized for empirical investigation?

- What are the causes and consequences of generic frames regarding individual behavior and/or social movements?

- Which attributes of visual stimuli (e.g. content, style, symbolism, ideology (Rodriguez & Dimitrova, 2011) are conceptually cohesive with the language-based research paradigm of framing?

On the substantive level, the context of “Food Supply Chain” (FSC) will further delimit the research area. Agri-food-systems are of high relevance regarding various sustainability dimensions (FAO, 2022; Messerli et al., 2019; Penker et al., 2023). By featuring sustainability in the FSC as an object of investigation, the research project may also allow insights into substantive questions such as:

- Which distinct mental frames of “sustainability” do actors of the FSC (e.g. Suppliers, Producers, Retailers, Policy Makers …) employ?

- How do different organizational environments of the FSC (e.g. farmer / consumer cooperatives, political parties, marketing service departments …) influence mental frames?

- Which visual / generic frames of sustainability in the FSC prevail?

- Which visual / generic frames do actors of the FSC perceive as supportive or inhibitive for transitions to sustainability?

In sum, frames create meaning, influence attitudes and guide action (Bateson, 1972; Gamson & Modigliani, 1989; Goffman, 1974). Answering some of the above questions can thus contribute to the understanding of human behavior, social change and collective action. Consequently, those insights may help to design and embark on pathways towards sustainable futures.

References

Barr, S., & Gilg, A. (2006). Sustainable lifestyles: Framing environmental action in and around the home. Geoforum, 37(6), 906–920. doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.05.002

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Collected Essays in Anthropology, Psychiatry, Evolution, and Epistemology. University of Chicago Press.

Béné, C., Oosterveer, P., Lamotte, L., Brouwer, I. D., de Haan, S., Prager, S. D., Talsma, E. F., & Khoury, C. K. (2019). When food systems meet sustainability – Current narratives and implications for actions. World Development, 113, 116–130. doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.08.011

Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing Processes and social movements: An Overview and Assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1974), 611–639.

Bock, M. A. (2020). Theorising visual framing: contingency, materiality and ideology. Visual Studies, 35(1), 1–12. doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2020.1715244

Brüggemann, M., & D’Angelo, P. (2018). Defragmenting News Framing Research: Reconciling Generic and Issue-Specific Frames. In P. D’Angelo (Ed.), Doing News Framing Analysis II: Empirical and theoretical perspectives (2. Auflage, pp. 90–111). Taylor & Francis Group. doi.org/10.4324/9781315642239-2

Chong, D., & Druckman, J. N. (2007). Framing Theory. Annual Review of Political Science, 10, 103–126. doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054

Coleman, R. (2009). Framing the Pictures in Our Heads: Exploring the Framing and Agenda-Setting Effects of Visual Images. In P. D’Angelo & J. A. Kuypers (Eds.), Doing News Framing Analysis: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives (1st editio, p. 30). Routledge.

Crompton, T., Brewer, J., Chilton, P., & Kasser, T. (2010). Common Cause: The Case for Working with our Cultural Values. self-published by WWF. doi.org/10.1017/s0084255900021367

D’Angelo, P. (2018a). Preface. In P. D’Angelo (Ed.), Doing News Framing Analysis II: Empirical and theoretical perspectives (2. Auflage, pp. xvii--xxi). Taylor & Francis Group. doi.org/10.4324/9781315642239-2

D’Angelo, P. (2018b). Prologue – A Typology of Frames in News Frame Analysis. In P. D’Angelo (Ed.), Doing News Framing Analysis II: Empirical and theoretical perspectives (2. Auflage, pp. xxiii–xl). Taylor & Francis Group. doi.org/10.4324/9781315642239-2

Dahinden, U. (2018). Framing: Eine integrative Theorie der Massenkommunikation. Herbert von Halem Verlag. doi.org/10.5771/1615-634x-2007-2-289

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4).

Entman, R. M. (2007). Framing Bias: Media in the Distribution of Power. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 163–173. doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00336.x

FAO. (2022). The State of Food and Agriculture 2022.

Gamson, W. A., & Modigliani, A. (1989). Media Discourse and Public Opinion on Nuclear Power: A Constructionist Approach. American Journal of Sociolog, 95, 1–37.

Geise, S., & Lobinger, K. (Eds.). (2013). Visual Framing. Perspektiven und Herausforderungen der visuellen Kommunikationsforschung. Herbert von Halem Verlag.

Geise, Stephanie, & Baden, C. (2015). Putting the image back into the frame: Modeling the linkage between visual communication and frame-processing theory. Communication Theory, 25(1), 46–69. doi.org/10.1111/comt.12048

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis – An Essay on the Organization of Experience (2nd Ed.). Harper & Row.

Guenther, L., Jörges, S., Mahl, D., & Brüggemann, M. (2023). Framing as a Bridging Concept for Climate Change Communication: A Systematic Review Based on 25 Years of Literature. Communication Research, 1–25. doi.org/10.1177/00936502221137165

Hallahan, K. (1999). Seven models of framing: Implications for public relations. Journal of Public Relations Research, 11(3), 205–242. doi.org/10.1207/s1532754xjprr1103_02

Iorgoveanu, A., & Corbu, N. (2011). No Consensus on Framing? Towards an Integrative Approach to Define Frames Both as Text and Visuals. Romanian Journal of Communication and Public Relations, 14(3), 91–102.

IPCC. (2021). Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change – Accelerating the transition in the context of sustainable development. In Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Janoušková, S., Hák, T., Nećas, V., & Moldan, B. (2019). Sustainable development-A poorly communicated concept by mass media. Another challenge for SDGs? Sustainability (Switzerland), 11(11), 1–20. doi.org/10.3390/su11113181

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1984). Choices, values, and frames. American Psychologist, 39(4), 341–350. doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803475.002

Matthes, J. (2009). What’s in a Frame? A Content Analysis of Media Framing Studies in the World’s Leading Communication Journals, 1990-2005. Journalism Mass Communication Quarterly, 86(2), 349–367.

Matthes, J., & Kohring, M. (2008). The content analysis of media frames: Toward improving reliability and validity. Journal of Communication, 58(2), 258–279. doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00384.x

Messerli, P., Murniningtyas, E., Eloundou-Enyegue, P., Foli, E. G., Furman, E., Glassman, A., Licona, G. H., Kim, E. M., Lutz, W., Moatti, J.-P., Richardson, K., Saidam, M., Smith, D., Kazimieras Staniškis, J., & van Ypersele, J.-P. (2019). The Future is Now – Science for Achieving Sustainable Development. In Global Sustainable Development Report 2019. United Nations. doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-240-81711-8.00010-4

Müller, M. G. (2013). “You cannot unsee a picture!” Der Visual-Framing-Ansatz in Theorie und Empirie. In Stephanie Geise & K. Lobinger (Eds.), Visual Framing. Perspektiven und Herausforderungen der Visuellen Kommunikationsforschung (pp. 19–41). Herbert von Halem Verlag.

Ness, B. (2020). Approaches for Framing Sustainability Challenges: Experiences from Swedish Sustainability Science Education. In S. Kudo & T. Mino (Eds.), Framing in Sustainability Science – Theoretical and Practical Approaches (1st ed., pp. 34–53). Springer Open. doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-9061-6_1

O’Neil, M., & Kendall-Taylor, N. (2018). Changing the Story: Reflections on Applied News Framing Analysis. In P. D’Angelo (Ed.), Doing News Framing Analysis II: Empirical and theoretical perspectives (2., pp. 51–68). Taylor & Francis Group. doi.org/10.4324/9781315642239-2

O’Neill, S., & Schäfer, M. S. (2018). Frame Analysis in Climate Change Communication. In M. C. Nisbet, S. S. Ho, E. Markowitz, S. O’Neil, M. S. Schäfer, & J. Thaker (Eds.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of Climate Change Communication. Oxford University Press.

Penker, M., Brunner, K. M., & Plank, C. (2023). Kapitel 5: Ernährung. In C. Görg, V. Madner, A. Muhar, A. Novy, A. Posch, K. Steininger, & E. Aigner (Eds.), APCC Special Report: Strukturen für ein klimafreundliches Leben (APCC SR Klimafreundliches Leben) (pp. 1–37). Springer Spektrum.

Reese, S. D. (2018). Foreword. In P. D’Angelo (Ed.), Doing News Framing Analysis II: Empirical and theoretical perspectives (2. Auflage, pp. xiii--xvi). Taylor & Francis Group. doi.org/10.4324/9781315642239-2

Rodriguez, L., & Dimitrova, D. V. (2011). The levels of visual framing. Journal of Visual Literacy, 30(1), 48–65. doi.org/10.1080/23796529.2011.11674684

Rust, N. A., Jarvis, R. M., Reed, M. S., & Cooper, J. (2021). Framing of sustainable agricultural practices by the farming press and its effect on adoption. Agriculture and Human Values, 1(0123456789). doi.org/10.1007/s10460-020-10186-7

Scheufele, B. (2004). Framing-effects approach: A theoretical and methodological critique. Communications, 29, 401–428.

Scheufele, D. A., & Iyengar, S. (2014). The state of framing research: A call for new directions. In The Oxford handbook of political communication (pp. 619–632). Oxford University Press. doi.orghttps://doi.org/10.1093/oxfor dhb/9780199793471.001.0001

Scheufele, Dietram A., & Tewksbury, D. (2007). Framing, Agenda Setting, and Priming: The Evolution of Three Media Effects Models. Journal of Communication, 57, 9–20. doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00326.x

Svensson, A., & Wahlström, M. (2023). Climate change or what? Prognostic framing by Fridays for Future protesters. Social Movement Studies, 22(1), 1–22. doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2021.1988913

University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna. (2023). Doctoral School Transitions to sustainability: Research. Boku.Ac.At. boku.ac.at/docservice/doktoratsstudien/doktoratsschulen/transitions-to-sustainability-t2s/research

Van Gorp, B. (2009). Strategies to take subjectivity out of framing analysis. Doing News Framing Analysis: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives, 84–109. doi.org/10.4324/9780203864463

Van Gorp, B., & van der Goot, M. J. (2012). Sustainable Food and Agriculture: Stakeholder’s Frames. Communication, Culture & Critique, 5(2), 127–148. doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-9137.2012.01135.x

Wardekker, A., & Lorenz, S. (2019). The visual framing of climate change impacts and adaptation in the IPCC assessment reports. Climatic Change, 156(1–2), 273–292. doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02522-6

Wehling, E. (2018). Politisches Framing: Wie eine Nation sich ihr Denken einredet – und daraus Politik macht (1. Auflage). Ullstein.

Ziem, A. (2018). Frames interdisziplinär: zur Einleitung. In A. Ziem, L. Inderelst, & D. Wulf (Eds.), Frames interdisziplinär: Modelle, Anwendungsfelder, Methoden. dup.