Despite the freezing temperatures, the atmosphere was warm and welcoming at the seminar on Automated Cars and their Consequences for Planning. The seminar took place on April 27th and 28th in Admont in the Gesäuse Mountains. It was organised by the Austrian Research Association for Roads, Railways and Transport (FSV) (Österreichische Forschungsgesellschaft Straße – Schiene – Verkehr) in cooperation with the Institute for Transport Studies from the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna (BOKU). Representatives from public administration, research and planning spoke and discussed potentials, risks and challenges emerging from automated driving, presenting their different points of view.

After the opening by Roman Klementschitz from the Institute for Transport Studies at BOKU, the first block focused on the ‘state of the art’, current frameworks and first experiences with automated cars. Michael Nikowitz, from the Austrian Ministry for Transport, Innovation and Technology (BMVIT), explained how important public funding was for implementing the opportunities emerging from automated cars. He presented different research funds and explained the development of testing sites, which will enable extensive testing of automated cars. Additionally, he emphasised that merely enabling automated driving was not the testing sites’ primary point. The goal was rather to gain insights for future planning, which can only be achieved by real-life experience.

Karl Rehrl from Salzburg Research talked about first experiences with the use of self-driving minibuses. For him, the real potential lies within the so-called ‘last mile’. The minibus used is produced by Navya and is classified as ‘4 SAE’. It recognises traffic regulations and navigates autonomously around obstacles. Such vehicles have to be trained fully manually. Furthermore, in this stage of development, active intervention by a human driver might be required. This means that an accompanying person must be available at all times.

The next speaker, Thomas Hader from the Vienna Chamber of Labour, presented a rather critical point of view. He considers the ongoing automation to be a one-sided development, mainly driven by IT corporations. Concerning the employee, he fears for job losses and other negative impacts through growing competition within the transport sector. He claims that new business models – such as for example any form of consuming while driving – would stand in stark contrast to the primary goal of autonomous cars: the conservation and protection of resources. Pointing out the danger of mobility becoming a purpose in itself, he warns about a significant increase in traffic.

Iris Eisenberger from the Institute of Law at BOKU talked about challenges and novelties in law. Following the current legal framework, SAE level 0 – 2 vehicles do not pose any legal difficulties. On the contrary, vehicles from SAE level 3 onward will require regulatory adjustments.

Generally, the legal difficulties, and thus the need for regulatory intervention, increases with each step towards more automation. For Eisenberger, a particular issue lies within the ‘Vertrauensgrundsatz’ – the ‘principle of trust’ – that Austrian traffic law is based upon. As this principle has its roots in human behaviour, it seems rather difficult to apply to automated vehicles. Nevertheless, she sees a lot of potential within automated vehicles and is convinced that rising challenges can be met appropriately.

The second block focused on the future prospects of automated driving. Mathias Mitteregger from the Institute of Architecture and Spatial Planning at the Technical University of Vienna is opposed to using the term ‘disruptive technology’ when referring to automated driving. He argues that automated driving is only in its formative phase, thus in the very beginning of its development. As with every technology, automated driving will be defined through its societal use. By formulating ‘Use Cases’, his project AVENUE 21 tries to understand how automated driving can be located within the socio-technical systems of cities and how it can serve the needs of different users.

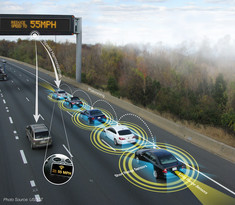

According to Udo Schüppel, psychologist at the Fahrzeugsystemdaten GmbH (FSD), the Central Agency for the Periodic Technical Inspection of Road Vehicles, the interconnection of vehicles plays a central role along with automation. He portrayed new forms of mobility on their way to automated driving and illustrated specific applications such as Highway Chauffeur, Platooning, automated valet parking and driverless delivery cars in computer simulations. By developing infrastructure accordingly, vehicle manufacturers or even cities themselves could become mobility service providers. Schüppel sees the major challenges lying within the areas of liability, data protection, data security and the human-machine interaction.

Silvia Rief from the Institute of Sociology at the University of Innsbruck opened the third block with a talk about the social and societal dimensions of automated driving. She follows the basic idea that technologies like automated driving interfere with socialisation processes by changing or creating forms of social relationships. She provided different socio-technical scenarios or ‘scripts’ of automated driving: Evolution (the enhancement of individual transportation), Revolution (new business models) and Transformation (Mobility on Demand). Every script could influence societal interdependencies and interactions differently. Which scenarios will establish themselves is not yet clear. A coexistence or combination might characterise the initial phase. For long-term development, infrastructural and funding decisions set in motion at the beginning could be decisive.

Tobias Haider, CEO of UbiGo, explained that common use is key to utilising positive potentials brought by automation, such as road safety, social inclusion and environmental protection, in the best way possible. Especially within rural areas, automation could ease or enable the use of socalled ‘shared mobility’. Compared to urban areas, these have a greater need for such forms of mobility, as a growing share of the population is no longer capable of using a vehicle autonomously. Additionally, Haider sees potential for ecological improvement, as individual transportation is currently dominant in rural areas.

Maria Juschten and Reinhard Hössinger, of the Institute for Transport Studies at BOKU, reviewed the influence of automated driving on traffic and mobility. They stated that new control elements are necessary to harmonise automated driving with current transportation policies. Additionally, they emphasised the importance of counteracting the steady rise of individual transportation and improving traffic efficiency. The former goal could be reached by supporting public transport and the integration of individual traffic into public transportation, the latter by reducing individual mobility and intensifying support of electric mobility. Concluding, the two asked the audience how autonomous vehicles should participate in traffic and who should set the required parameters: technology developers, experts, interest groups, politics or citizens. The audience voted by using their smartphones. Especially for the question of fluid versus safe traffic, the audience thought the ‘experts’ group to be the most competent.

Petra Jens from the Mobility Agency Vienna fears that automated cars will further reduce pedestrians in public space. Therefore, she asked what future interactions in road traffic should look like. Will traffic be open to everyone? Do humans have to be interconnected electronically to participate in traffic? Jens warns about ‘traffic education’ designed by industrial interests. The pedestrian-friendliness of a city is important to its quality of living. With this in mind, pedestrians should remain a central issue in traffic planning. In the end, planning for specific consequences must influence the development of automated driving, not vice versa.

As the seminar progressed, it became clear that automated driving is a technology whose development has just begun. Whether seen from a technical, legislative, social or traffic-planning point of view, it is anything but obvious which direction this technology will take and what are the consequences that come with it. Despite this uncertainty, about one point the participants displayed complete consensus – that it is more than time to have a broad, open discourse in order to actively influence and shape these developments.

Sophia San Nicolò, May 2017

Translated by Annemarie Hofer

-

© U.S. Department of Transportation (Public Domain Mark 1.0)