Mathematical group hierarchies

A group is a simple mathematical structure that describes symmetries, like those of a geometric figure, a pattern on a wallpaper, or a crystal. For example, the cyclic group C3 describes the three states of rotating an equilateral triangle; the cyclic group C4 describes the four states of rotating a square; the Klein four-group K4 describes the four states of a rectangle that can be rotated by 180 degrees or flipped. There exists one group of order three (C3), but two groups of order four (C4 and K4). For the number N(k) of groups (up to isomorphism) of order k it means N(3)=1 and N(4)=2. But to understand N(k) for general k is puzzling. Particularly many groups exist of order a power of two, like N(64) = 267, or, for example, more than 99% of groups of order less than 2000 are of order k=1024. A hint to the fundamental interest in this question is the fact that it is the very first sequence in the well-known "Online encycolpedia of integer sequences":

oeis.org/A000001

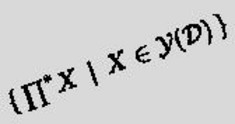

An immediate upper bound for N(k) is 2^k, since no more Cayley tables can exist. This bound is not helpful for finite groups, but it is sharp for infinite groups: there exist 2^k pairwise non-isomorphic groups of cardinality k for every infinite k, that is, N(k) = 2^k. In 1974 Shelah showed that for each fixed infinite cardinality k, this infinitude of 2^k pairwise non-isomorphic groups can be obtained even with pairwise non-embeddable groups. If groups of distinct sizes are considered, it is not ruled out that the smaller group is embeddable in the larger group. In 2025 Gerald Kuba from BOKU University, Institute of Mathematics, carried out a new construction with a certain, rather large cardinal bound, such that for any pair of distinct infinite groups G and H of sizes up to this bound, be the sizes equal or not, G is not embeddable in H.

arxiv.org/abs/2401.17962