Dynamics and Flow Behavior of Natural Debris Flows: From Velocity Profiling to Rheological Insights

Supervisor: Roland KAITNA

Project assigned to: Maximilian ENDER

Introduction

Debris flows can be defined as highly variable concentrated sediment-water mass flows (Hungr et al., 2014; Iverson, 1997; Takahashi, 2007), whereby the solid volume fraction can easily reach values up to 40 to 90 % (Lavigne and Suwa, 2004). The main trigger mechanisms are predominantly short-duration convective precipitation events (Corominas et al., 1996; Guzzetti et al., 2008; Nikolopoulos et al., 2017; Wieczorek and Glade, 2005), although snowmelt (Decaulne et al., 2005; Mostbauer et al., 2018), dam break effects (Capart et al., 2001; Cui et al., 2010; Fang et al., 2019; Sattar et al., 2022) or landslides (Gabet and Mudd, 2006; Iverson et al., 1997; Sassa and Wang, 2005) can also play a role as initiation mechanisms. The process follows generally a steep channel (“torrent” or “creek”) and often consists of a variable number of surges which can obtain high velocities approaching 10 ms-1 (Nagl et al., 2020). This leads to highly destructive power that endangers settlements, infrastructure and human lives (Castelli et al., 2023; Dowling and Santi, 2014; Haque et al., 2019; Schlögl et al., 2021). Sediment grain sizes can include a wide range of magnitudes (Kaitna et al., 2014; Rickenmann, 2016), are often subject to a wide dispersion and can vary greatly within a single event or during different debris-flow events in the same catchment (Arattano and Franzi, 2004; Hübl, 2018; Marchi and Cavalli, 2007; Rickenmann, 1997; Theule et al., 2012). The flow behavior is strongly dependent on the respective grain size distribution of the mixture (Iverson et al., 2010). While the front of a typical debris flow usually consists of coarse particles, the body is made up of more liquid components, typically with smaller grain sizes in suspension (Coussot and Meunier, 1996; Hungr, 2005; Zhou and Ng, 2010).

A key factor in investigating the flow behavior of debris flows is the consideration of flow resistance. One fundamental approach for assessing flow resistance, besides modelling, involves examining velocity distributions, as both mean velocities and velocity fluctuations provide insights into the bulk flow dynamics of the mixture (Du et al., 2021; Kaitna et al., 2014; Lanzoni et al., 2017; Larcher et al., 2007). Since velocity plays a decisive role in the erosion, transport, and deposition behavior of debris flows, estimating vertical velocity distributions provides a robust basis for analyzing internal deformation processes and conducting subsequent rheological analyses.

The focus of this PhD thesis is to derive vertical velocity profiles in natural debris flows, investigate the dynamics within and between different debris flows and carry out rheological interpretations of the observed flow behavior. This leads to the following research questions:

- How can the accuracy and reliability of deriving vertical velocity profiles in natural debris flows be optimized with respect to parameter sensitivity, measurement system performance, and achievable temporal resolution?

- How can flow behavior in debris flows be described based on observed vertical velocity profiles, and how do these profiles relate to material properties and laboratory observations?

- Can consistent patterns in vertical velocity profiles, wave dynamics, and stress conditions be identified across different natural debris flows, providing a basis for rheological interpretations?

Methods

(a) Study area and monitoring station

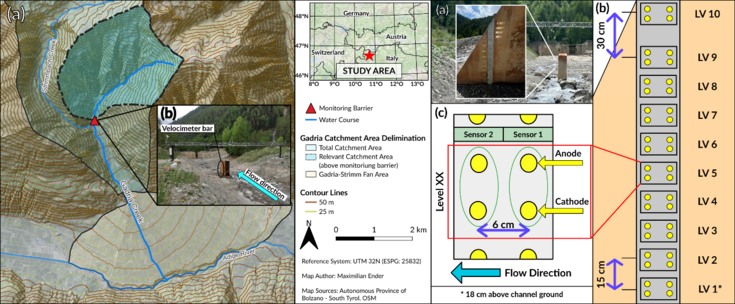

Figure 1: Overview of the Gadria catchment area (left) and the setup of the velocimeter (right).

The catchment of Gadria creek is located in the upper Vinschgau/Venosta valley in the Autonomous Province of Bolzano – South Tyrol, Italy. The Gadria-Strimm creek system has formed an exceptionally large fan (megafan), which covers an area of over 10 km² and has had a significant impact on the postglacial landscape evolution of the glacially shaped main valley (Comiti et al., 2014; Jarman et al., 2011). The catchment area lies south of the Alpine ridge, within the Oetztal Unit, a subrange of the Central Eastern Alps. The interplay of large volume of fragmented bedrock, glacial deposits, and high relief energy together with convective precipitation events between June and September (c.f. Della Chiesa et al., 2014) leads to the regular occurrence of debris flows with an annual frequency of approximately 1 to 2 events (Cavalli et al., 2013). Climatologically, the field site is located within a pronounced alpine dry region, resulting from the central Alpine position of the upper Vinschgau/Venosta valley and the associated orographic rain shadow effects (Dell’Agnese et al., 2015), with annual precipitation amounts below 600 mm in the valley ground (Brugnara et al., 2012).

The monitoring station is situated at the fan apex at 1,500 m a.s.l. It consists, on the one hand of a concrete barrier, located in the middle of the channel bed, constructed in 2017. On the other hand, a meteorological station is installed on the orographic left channel bank, and an iron bridge spans the channel upstream of the monitoring barrier. The monitoring installations enable temporal high-resolution measurements of debris-flow parameters, including flow depth, impact forces, normal and shear stresses, and pore fluid pressure. The full details of the monitoring station setup including a description of all measured parameters can be found in (Nagl et al., 2020).

(b) Derivation of vertical velocity distributions

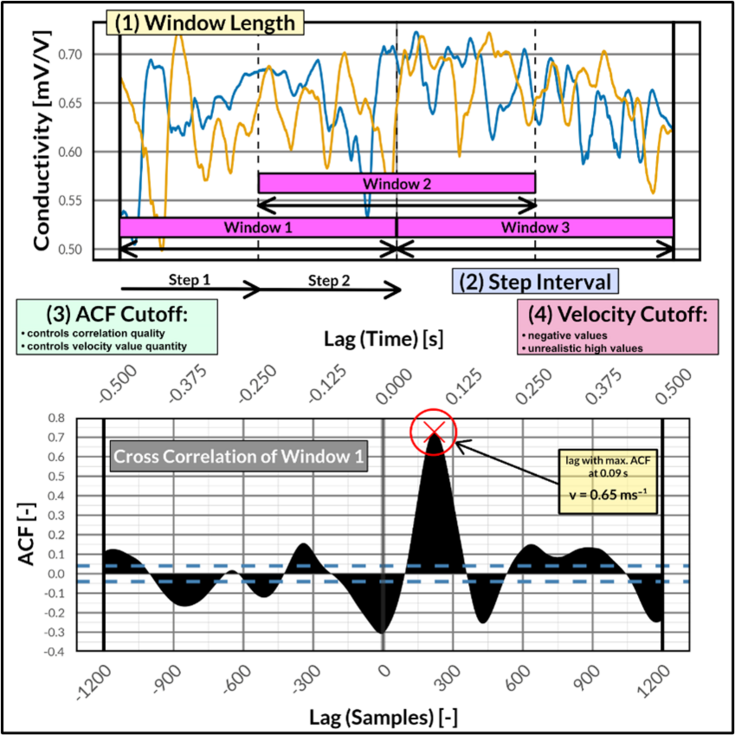

Figure 2: Exemplary cross-correlation and overview of parameters of interest for the cross-correlation function for one sensor pair level: Window length, step interval, ACF cutoff and velocity cutoff.

The use of cross-correlation to derive flow velocities from sensor signals is grounded in a broad range of experimental studies (e.g., Ahn et al., 1991; Boateng and Barr, 1997; Bowman and Take, 2015; Dent et al., 1998; Kaitna et al., 2014; McElwaine and Tiefenbacher, 2003; Schaefer et al., 2010; Schaefer and Bugnion, 2013; Sovilla et al., 2014; Tiefenbacher and Kern, 2004; Wei et al., 2012), all of which share the fundamental principle of deriving a time lag t between the two signals. Since the spatial offset between the signal sensors is known, velocities can be determined via the relationship v = s/t.

In natural debris flows, the method of cross-correlation time-shifted sensor signals, has been applied using seismic and ultrasonic sensors (Arattano and Marchi, 2005). Nagl et al., 2020 successfully transferred the technique of correlating paired conductivity sensors from laboratory setups (Kaitna et al., 2014) to field measurements and demonstrated that vertical velocity profiles can be derived in natural debris flows at the Gadria monitoring station. To resolve the temporal evolution of velocity, a floating time window is applied to the conductivity signal data. For each window, a cross-correlation is performed across all sensor levels of the velocimeter bar, yielding a potential representative velocity for each level and window. Velocity estimates are obtained for sensor levels contacted by the passing debris-flow mass within the respective time window. This approach provides a time series of velocity values rather than a single average over the entire measurement period.

Preliminary results

(a) Parameter sensitivity analysis

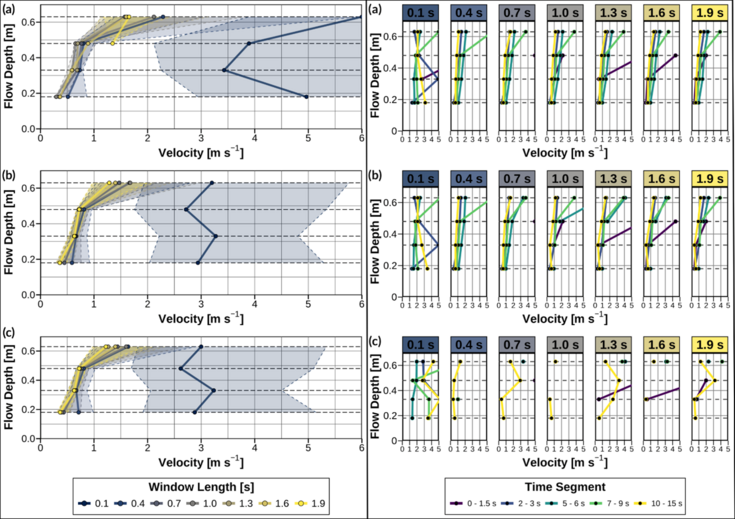

As key parameters for a robust cross-correlation-based derivation of velocity distributions of natural debris flows at the Gadria creek, the length of the floating window, the overlap of the floating window, a cutoff value for the ACF (correlation coefficient), and a cutoff interval for the correlated velocities (to exclude unrealistic velocity estimates) are defined and subjected to a sensitivity analysis. For this purpose, a distinction is made between “steady” flow segments, characterized by minimal changes in material composition and flow depth, and “unsteady” flow segments, which exhibit, strong, temporal short-term variations in material composition and flow depth (e.g., during waves).

The results indicate that the ACF cutoff and the length of the floating window exert the strongest influence on the derived velocity distributions, while the overlap interval and the velocity interval play a secondary role. Additionally, there exists a lower-bound velocity that cannot be undershot. This limit arises from the constraints imposed by the cross-correlation method, the measurement frequency, and the sensor spacing. It is primarily dependent on the floating window length and increases as the window length decreases

Figure 3: Velocity profiles in a steady flow segment (left) and an unsteady flow segment (right) for different window lengths for (a) an ACF cutoff of 0.25, (b) an ACF cutoff of 0.50, and (c) for an ACF cutoff of 0.75.

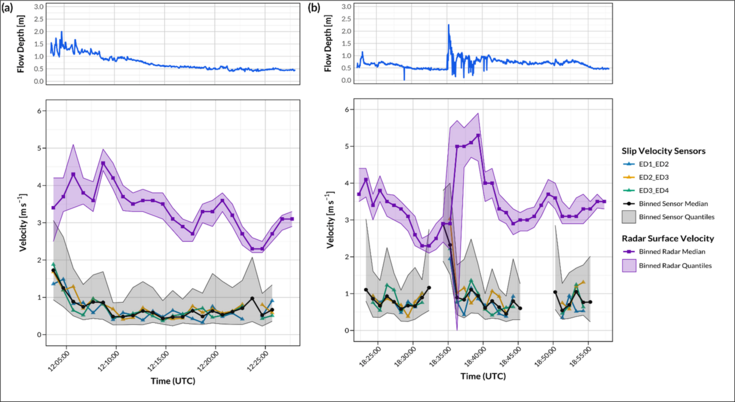

(b) Basal slip velocities

A similar sensor setup was installed at the Lattenbach creek in Tyrol, Austria, on the channel bed with the aim of obtaining more detailed information on basal slip velocities in natural debris flows. Some laboratory experiments indicate the presence of basal sliding in debris flows (e.g., Sanvitale and Bowman, 2010; Taylor-Noonan et al., 2022), whereas most simple shear models assume a no-slip condition (e.g., Berzi and Jenkins, 2008; Garres-Díaz et al., 2020; Luna et al., 2012; Pastor et al., 2021; Pudasaini, 2012). Initial analyses of sensor data for two recent debris-flow events reveal the continuous presence of a basal slip velocity.

For more details, see: https://egusphere.copernicus.org/preprints/2025/egusphere-2025-4872/.

Figure 4: Slip velocity measurements for two debris-flow events at Lattenbach creek.

References

Ahn, H., Brennen, C. E., and Sabersky, R. H.: Measurements of Velocity, Velocity Fluctuation, Density, and Stresses in Chute Flows of Granular Materials, Journal of Applied Mechanics, 58, 792–803, doi.org/10.1115/1.2897265, 1991.

Arattano, M. and Franzi, L.: Analysis of different water-sediment flow processes in a mountain torrent, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 4, 783–791, doi.org/10.5194/nhess-4-783-2004, 2004.

Arattano, M. and Marchi, L.: Measurements of debris flow velocity through cross-correlation of instrumentation data, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 5, 137–142, doi.org/10.5194/nhess-5-137-2005, 2005.

Berzi, D. and Jenkins, J. T.: A theoretical analysis of free-surface flows of saturated granular–liquid mixtures, J. Fluid Mech., 608, 393–410, doi.org/10.1017/S0022112008002401, 2008.

Boateng, A. A. and Barr, P. V.: Granular flow behaviour in the transverse plane of a partially filled rotating cylinder, J. Fluid Mech., 330, 233–249, doi.org/10.1017/S0022112096003680, 1997.

Bowman, E. T. and Take, W. A.: The runout of chalk cliff collapses in England and France—case studies and physical model experiments, Landslides, 12, 225–239, doi.org/10.1007/s10346-014-0472-2, 2015.

Brugnara, Y., Brunetti, M., Maugeri, M., Nanni, T., and Simolo, C.: High‐resolution analysis of daily precipitation trends in the central Alps over the last century, Intl Journal of Climatology, 32, 1406–1422, doi.org/10.1002/joc.2363, 2012.

Capart, H., Young, D. ‐L., and Zech, Y.: Dam‐Break Induced Debris Flow, in: Particulate Gravity Currents, edited by: McCaffrey, W., Kneller, B., and Peakall, J., Wiley, 149–156, doi.org/10.1002/9781444304275.ch11, 2001.

Castelli, F., Foti, E., Lentini, V., and Pirulli, M.: Risk Assessment of Transport Linear Infrastructures to Debris Flow, E3S Web of Conf., 415, 07004, doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202341507004, 2023.

Cavalli, M., Trevisani, S., Comiti, F., and Marchi, L.: Geomorphometric assessment of spatial sediment connectivity in small Alpine catchments, Geomorphology, 188, 31–41, doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2012.05.007, 2013.

Comiti, F., Marchi, L., Macconi, P., Arattano, M., Bertoldi, G., Borga, M., Brardinoni, F., Cavalli, M., D’Agostino, V., Penna, D., and Theule, J.: A new monitoring station for debris flows in the European Alps: first observations in the Gadria basin, Nat Hazards, 73, 1175–1198, doi.org/10.1007/s11069-014-1088-5, 2014.

Corominas, J., Remondo, J., Farias, P., Estevao, M., Zézere, J., Díaz de Terán, J., Dikau, R., Schrott, L., Moya, J., and González, A.: Debris Flow, in: Landslide recognition: report n °1 of the European commission environment programme contract n °EV5V-CT94-0454 identification, movement and causes, J. Wiley and sons, Chichester New York Brisbane [etc.], 1996.

Coussot, P. and Meunier, M.: Recognition, classification and mechanical description of debris flows, Earth-Science Reviews, 40, 209–227, doi.org/10.1016/0012-8252(95)00065-8, 1996.

Cui, P., Dang, C., Cheng, Z., and Scott, K. M.: Debris Flows Resulting From Glacial-Lake Outburst Floods in Tibet, China, Physical Geography, 31, 508–527, doi.org/10.2747/0272-3646.31.6.508, 2010.

Decaulne, A., Sæmundsson, Þ., and Petursson, O.: Debris flow triggered by rapid snowmelt: a case study in the glei .arhjalli area, northwestern iceland, Geografiska Annaler: Series A, Physical Geography, 87, 487–500, doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3676.2005.00273.x, 2005.

Della Chiesa, S., Bertoldi, G., Niedrist, G., Obojes, N., Endrizzi, S., Albertson, J. D., Wohlfahrt, G., Hörtnagl, L., and Tappeiner, U.: Modelling changes in grassland hydrological cycling along an elevational gradient in the Alps, Ecohydrology, 7, 1453–1473, doi.org/10.1002/eco.1471, 2014.

Dell’Agnese, A., Brardinoni, F., Toro, M., Mao, L., Engel, M., and Comiti, F.: Bedload transport in a formerly glaciated mountain catchment constrained by particle tracking, Earth Surf. Dynam., 3, 527–542, doi.org/10.5194/esurf-3-527-2015, 2015.

Dent, J. D., Burrell, K. J., Schmidt, D. S., Louge, M. Y., Adams, E. E., and Jazbutis, T. G.: Density, velocity and friction measurements in a dry-snow avalanche, Ann. Glaciol., 26, 247–252, doi.org/10.3189/1998AoG26-1-247-252, 1998.

Dowling, C. A. and Santi, P. M.: Debris flows and their toll on human life: a global analysis of debris-flow fatalities from 1950 to 2011, Nat Hazards, 71, 203–227, doi.org/10.1007/s11069-013-0907-4, 2014.

Du, C., Wu, W., and Ma, C.: Velocity profile of debris flow based on quadratic rheology model, J. Mt. Sci., 18, 2120–2129, doi.org/10.1007/s11629-021-6790-7, 2021.

Fang, Q., Tang, C., Chen, Z., Wang, S., and Yang, T.: A calculation method for predicting the runout volume of dam-break and non-dam-break debris flows in the Wenchuan earthquake area, Geomorphology, 327, 201–214, doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2018.10.023, 2019.

Gabet, E. J. and Mudd, S. M.: The mobilization of debris flows from shallow landslides, Geomorphology, 74, 207–218, doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2005.08.013, 2006.

Garres-Díaz, J., Bouchut, F., Fernández-Nieto, E. D., Mangeney, A., and Narbona-Reina, G.: Multilayer models for shallow two-phase debris flows with dilatancy effects, Journal of Computational Physics, 419, 109699, doi.org/10.1016/j.jcp.2020.109699, 2020.

Guzzetti, F., Peruccacci, S., Rossi, M., and Stark, C. P.: The rainfall intensity–duration control of shallow landslides and debris flows: an update, Landslides, 5, 3–17, 2008.

Haque, U., Da Silva, P. F., Devoli, G., Pilz, J., Zhao, B., Khaloua, A., Wilopo, W., Andersen, P., Lu, P., Lee, J., Yamamoto, T., Keellings, D., Wu, J.-H., and Glass, G. E.: The human cost of global warming: Deadly landslides and their triggers (1995–2014), Science of The Total Environment, 682, 673–684, doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.415, 2019.

Hübl, J.: Conceptual Framework for Sediment Management in Torrents, Water, 10, 1718, doi.org/10.3390/w10121718, 2018.

Hungr, O.: Classification and terminology, in: Debris-flow Hazards and Related Phenomena, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 9–23, doi.org/10.1007/3-540-27129-5_2, 2005.

Hungr, O., Leroueil, S., and Picarelli, L.: The Varnes classification of landslide types, an update, Landslides, 11, 167–194, doi.org/10.1007/s10346-013-0436-y, 2014.

Iverson, R. M.: The physics of debris flows, Reviews of Geophysics, 35, 245–296, doi.org/10.1029/97RG00426, 1997.

Iverson, R. M., Reid, M. E., and LaHusen, R. G.: DEBRIS-FLOW MOBILIZATION FROM LANDSLIDES, Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci., 25, 85–138, doi.org/10.1146/annurev.earth.25.1.85, 1997.

Iverson, R. M., Logan, M., LaHusen, R. G., and Berti, M.: The perfect debris flow? Aggregated results from 28 large‐scale experiments, J. Geophys. Res., 115, 2009JF001514, doi.org/10.1029/2009JF001514, 2010.

Jarman, D., Agliardi, F., and Crosta, G. B.: Megafans and outsize fans from catastrophic slope failures in Alpine glacial troughs: the Malser Haide and the Val Venosta cluster, Italy, SP, 351, 253–277, doi.org/10.1144/SP351.14, 2011.

Kaitna, R., Dietrich, W. E., and Hsu, L.: Surface slopes, velocity profiles and fluid pressure in coarse-grained debris flows saturated with water and mud, J. Fluid Mech., 741, 377–403, doi.org/10.1017/jfm.2013.675, 2014.

Lanzoni, S., Gregoretti, C., and Stancanelli, L. M.: Coarse‐grained debris flow dynamics on erodible beds, JGR Earth Surface, 122, 592–614, doi.org/10.1002/2016JF004046, 2017.

Larcher, M., Fraccarollo, L., Armanini, A., and Capart, H.: Set of measurement data from flume experiments on steady uniform debris flows, Journal of Hydraulic Research, 45, 59–71, doi.org/10.1080/00221686.2007.9521833, 2007.

Lavigne, F. and Suwa, H.: Contrasts between debris flows, hyperconcentrated flows and stream flows at a channel of Mount Semeru, East Java, Indonesia, Geomorphology, 61, 41–58, doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2003.11.005, 2004.

Luna, B. Q., Remaître, A., Van Asch, Th. W. J., Malet, J.-P., and Van Westen, C. J.: Analysis of debris flow behavior with a one dimensional run-out model incorporating entrainment, Engineering Geology, 128, 63–75, doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2011.04.007, 2012.

Marchi, L. and Cavalli, M.: Procedures for the Documentation of Historical Debris Flows: Application to the Chieppena Torrent (Italian Alps), Environmental Management, 40, 493–503, doi.org/10.1007/s00267-006-0288-5, 2007.

McElwaine, J. N. and Tiefenbacher, F.: Calculating Internal Avalanche Velocities from Correlation with Error Analysis, Surveys in Geophysics, 24, 499–524, doi.org/10.1023/B:GEOP.0000006079.89478.04, 2003.

Mostbauer, K., Kaitna, R., Prenner, D., and Hrachowitz, M.: The temporally varying roles of rainfall, snowmelt and soil moisture for debris flow initiation in a snow-dominated system, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 22, 3493–3513, doi.org/10.5194/hess-22-3493-2018, 2018.

Nagl, G., Hübl, J., and Kaitna, R.: Velocity profiles and basal stresses in natural debris flows, Earth Surf Processes Landf, 45, 1764–1776, doi.org/10.1002/esp.4844, 2020.

Nikolopoulos, E. I., Destro, E., Maggioni, V., Marra, F., and Borga, M.: Satellite Rainfall Estimates for Debris Flow Prediction: An Evaluation Based on Rainfall Accumulation–Duration Thresholds, Journal of Hydrometeorology, 18, 2207–2214, doi.org/10.1175/JHM-D-17-0052.1, 2017.

Pastor, M., Tayyebi, S. M., Stickle, M. M., Yagüe, Á., Molinos, M., Navas, P., and Manzanal, D.: A depth integrated, coupled, two-phase model for debris flow propagation, Acta Geotech., 16, 2409–2433, doi.org/10.1007/s11440-020-01114-4, 2021.

Pudasaini, S. P.: A general two‐phase debris flow model, J. Geophys. Res., 117, 2011JF002186, doi.org/10.1029/2011JF002186, 2012.

Rickenmann, D.: Sediment transport in Swiss torrents, Earth Surf. Process. Landforms, 22, 937–951, doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9837(199710)22:10<937::AID-ESP786>3.0.CO;2-R, 1997.

Rickenmann, D.: Methods for the Quantitative Assessment of Channel Processes in Torrents (Steep Streams), 0 ed., CRC Press, doi.org/10.1201/b21306, 2016.

Sanvitale, N. and Bowman, E. T.: Optical investigation through a flowing saturated granular material, in: Physical modelling in geotechnics: 7th ICPMG 2010, edited by: Ng, C. W. W., CRC, Boca Raton, 1279–1284, 2010.

Sassa, K. and Wang, G. H.: Mechanism of landslide-triggered debris flows: Liquefaction phenomena due to the undrained loading of torrent deposits, in: Debris-flow Hazards and Related Phenomena, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 81–104, doi.org/10.1007/3-540-27129-5_5, 2005.

Sattar, A., Haritashya, U. K., Kargel, J. S., and Karki, A.: Transition of a small Himalayan glacier lake outburst flood to a giant transborder flood and debris flow, Sci Rep, 12, 12421, doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-16337-6, 2022.

Schaefer, M. and Bugnion, L.: Velocity profile variations in granular flows with changing boundary conditions: insights from experiments, Physics of Fluids, 25, 063303, doi.org/10.1063/1.4810973, 2013.

Schaefer, M., Bugnion, L., Kern, M., and Bartelt, P.: Position dependent velocity profiles in granular avalanches, Granular Matter, 12, 327–336, doi.org/10.1007/s10035-010-0179-6, 2010.

Schlögl, M., Fuchs, S., Scheidl, C., and Heiser, M.: Trends in torrential flooding in the Austrian Alps: A combination of climate change, exposure dynamics, and mitigation measures, Climate Risk Management, 32, 100294, doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2021.100294, 2021.

Sovilla, B., McElwaine, J. N., and Louge, M. Y.: The structure of powder snow avalanches, Comptes Rendus. Physique, 16, 97–104, doi.org/10.1016/j.crhy.2014.11.005, 2014.

Takahashi, T.: Debris flow: mechanics, prediction and countermeasures, Taylor & Francis, Amsterdam, 2007.

Taylor-Noonan, A. M., Bowman, E. T., McArdell, B. W., Kaitna, R., McElwaine, J. N., and Take, W. A.: Influence of Pore Fluid on Grain-Scale Interactions and Mobility of Granular Flows of Differing Volume, Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface, 127, doi.org/10.1029/2022JF006622, 2022.

Theule, J. I., Liébault, F., Loye, A., Laigle, D., and Jaboyedoff, M.: Sediment budget monitoring of debris-flow and bedload transport in the Manival Torrent, SE France, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 12, 731–749, doi.org/10.5194/nhess-12-731-2012, 2012.

Tiefenbacher, F. and Kern, M. A.: Experimental devices to determine snow avalanche basal friction and velocity profiles, Cold Regions Science and Technology, 38, 17–30, doi.org/10.1016/S0165-232X(03)00060-0, 2004.

Wei, F., Yang, H., Hu, K., and Chernomorets, S.: Measuring internal velocity of debris flows by temporally correlated shear forces, J. Earth Sci., 23, 373–380, doi.org/10.1007/s12583-012-0258-1, 2012.

Wieczorek, G. F. and Glade, T.: Climatic factors influencing occurrence of debris flow, in: Debris-flow hazards and related phenomena, Springer Praxis publ, Berlin Chichester, 2005.

Zhou, G. G. D. and Ng, C. W. W.: Numerical investigation of reverse segregation in debris flows by DEM, Granular Matter, 12, 507–516, doi.org/10.1007/s10035-010-0209-4, 2010.